A UK first: Artemisia Gentileschi at the National Gallery

The National Gallery’s exhibition Artemisia was one of the long-awaited shows of 2020 and no postponement or interruption dampened the well-deserved excitement that built around it. The London institution’s significant acquisition in 2018 of Artemisia Gentileschi’s (1593–1654) Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (fig. 1), and the lack of a monographic exhibition devoted to her in the UK, contributed to impress on curator Letizia Treves the necessity for one such effort. The show featured thirty-six paintings covering the full span of Gentileschi’s peripatetic career and including many of her best-known and best-preserved works [1].

Forming a diverse group within her oeuvre, Artemisia’s self-portraits blurred the boundary between self-promotion and artistic practice, and her insertion in many of her paintings was noted by her contemporaries, who would have appreciated both her wit and her business-acumen. This inspired me to focus here on images of Artemisia, either by herself or by others, to consider their significance both within and beyond the span of her career.

A Roman artist

Born in Rome, Artemisia’s only teacher was her father, the celebrated painter Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639). As a woman she was not allowed to leave her home unsupervised and wander freely around the street, churches and palaces of the Holy City (she was also responsible for her three younger brothers). In spite of these limitations, Artemisia Gentileschi quickly developed into a competent painter, so skilled to inspire her father’s pride. Her earliest signed and dated work, the Suzanna and the Elders (Schloss Weißenstein), made when she was 17 years old, is an accomplished and original retelling of the familiar moral tale, from a female perspective.

The course of her life was drastically diverted when one of father’s associates, the well-connected painter Agostino Tassi, raped the young Artemisia, later promising to marry her. A promise he broke, leading to Orazio pressing charges against Tassi. The trial that followed was a public affair and resulted in Tassi’s sentencing to exile – a punishment that was never enforced. Soon after the trial it was Artemisia who left her native city in search of a fresh start, having married Pierantonio Stiattesi, a modest Florentine painter.

Florence 1613-1620

In Florence, Gentileschi becomes the first female member of the prestigious Accademia del Disegno. Probably soon after her arrival she executed her first known self-portrait, fashioning herself as a female martyr (fig. 2). The motif of the cloth loosely wrapped around the figure’s head helps to characterize the protagonist as a historical character while also relating to Artemisia’s own involvement with theatrical dress-up: she is said to have performed the role of a gypsy.

In her now famous self-portrait in the guise of the 4th-century Christian martyr, Saint Catherine of Alexandria (see fig. 1), she continued to play with self-fashioning and to blur the boundary between self-portraiture and historical depiction, by combining Catherine’s crown with the piece of fabric loosely wrapped around her head by way of a signature. Legend describes Saint Catherine as a philosopher and daughter of a prince of Egypt, who was tortured on the spiked wheel for refusing to renounce her Christian faith. Her martyrdom is symbolized by the palm branch she holds in her right hand.

One of the highlights of the show was the opportunity to see Artemisia’s four Florentine self-portraits in a glorious line-up. Technical analysis recently carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence, has shown that the National Gallery and Uffizi (fig. 3) versions of Saint Catherine are based on the same preparatory drawing or cartoon, and that this also constituted the starting point for the striking Self-portrait as a Lute Player in Hartford (fig. 4).

Back in Rome: Artemisia’s hand

Despite the demand for her paintings in Florence and her attempts to be seen as an artist of Tuscan lineage (she adopted the surname Lomi, after her paternal grandfather, a goldsmith), Artemisia was forced back to Rome by financial hardship. She also lost three of her five children. Comfort came, at least in part, from her love affair with the Florentine nobleman Francesco Maria Maringhi. The discovery in 2011, in the Archivio Storico Frescobaldi in Florence, of a group of letters written by Artemisia and her husband to Maringhi, reveals him as not only her lover, but also a confidant, intermediary and financial supporter for the rest of her life (the two met in Florence when they were both 24 years old).

Back in Rome from early 1620, Artemisia’s success grew. She became a sought-after portraitist and continue to develop her unique brand of Caravaggism. Together with the attention of patrons, the artistic community’s fascination with Artemisia as woman and artist developed, as attested by the many depictions of her likeness in paintings, drawings, prints and medals. Her contemporaries may have been aware of the misadventures of her youth but did not mention them. There was so much more about Artemisia deserving of praise: her wit, her talent, her beauty.

Simon Vouet’s painting of circa 1623-26 (fig. 5) portrays her as both elegant and committed to her trade, with a palette and brush in her left hand and a toccalapis (chalk holder) in her right. The prominently displayed gold medallion features a mausoleum, a witty play on words used to identify the illustrious sitter by referring to her namesake, Artemisia of Halicarnassus (d. 350 BC), who built the famous Mausolus, one of the wonders of the ancient world.

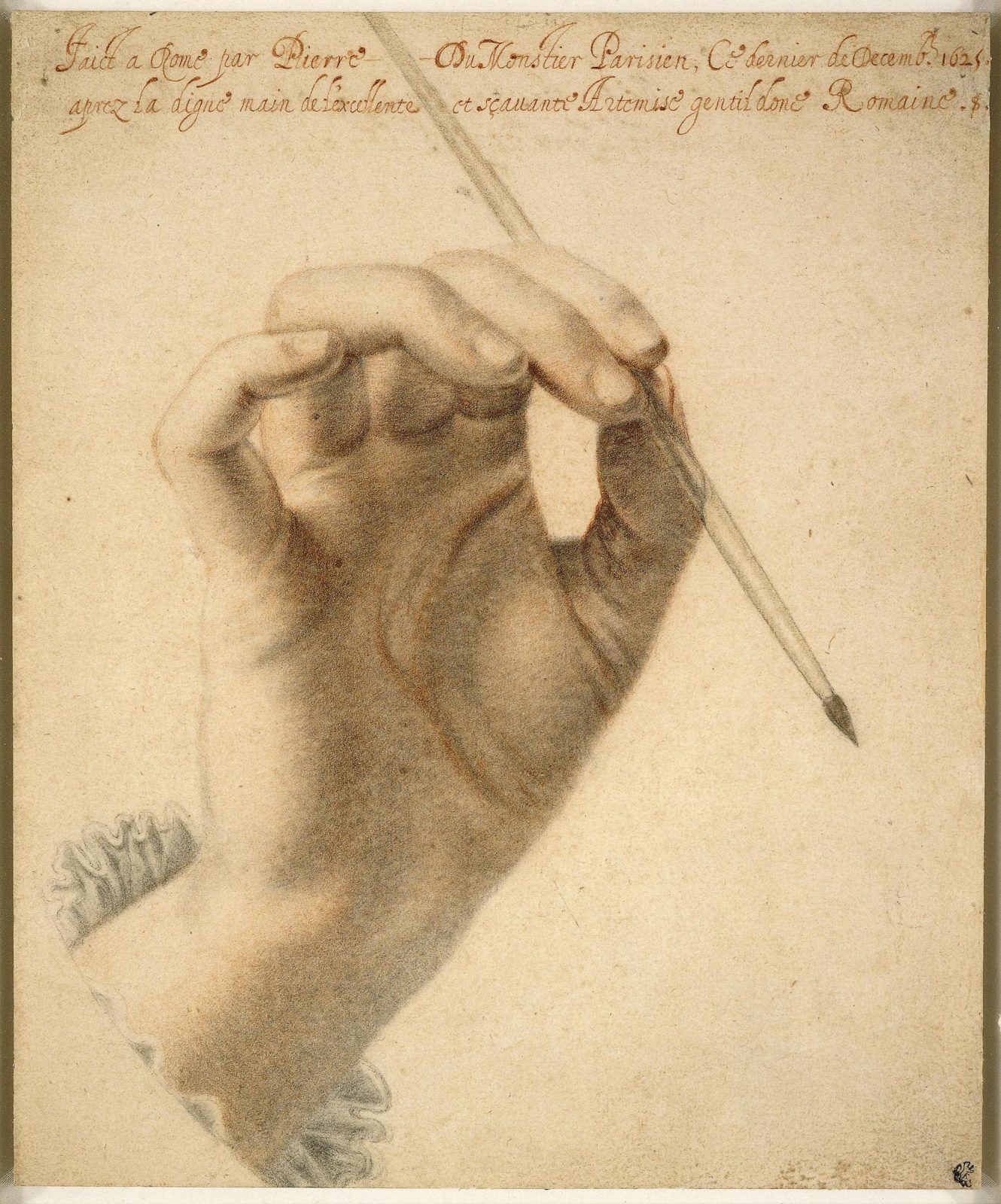

Not far from Vouet’s large portrait, visitors to the exhibition would encounter a chalk drawing by Pierre Dumonstier II, who, like Vouet, met Artemisia in Rome. This is a symbolic portrait of the artist, as it shows Artemisia’s right hand elegantly holding a brush (fig. 6). The inscription on the verso of the sheet translates as ‘The hands of Aurora are praised and renowned for their rare beauty. But this one is a thousand times more worthy for knowing how to make marvels that send the most judicious eyes into raptures.’

Venice, Naples, London: The spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman

Her notoriety was not enough to guarantee Artemisia’s life in Rome. Instead, after a brief stint in Venice where she painted her majestic Esther before Ahasuerus (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), she would be based in Naples for the rest of her life while constantly seeking the elusive support of foreign noble patrons.

Her short yet important sojourn in London in the late 1630s was celebrated in the last room of the National Gallery’s display. In London, she had the chance to reunite with her father and briefly collaborate with him on his last big commission, the ceiling paintings of the Queen’s House, in Greenwich (now at Marlborough House in London).

It was probably during her stay in London that Gentileschi painted one of her most iconic works, the Self-portrait as Pittura (fig. 7), “the quintessential Baroque version of the Allegory of Painting” [1]. It is based only in part on Cesare Ripa’s description in the Iconologia (fig. 8), note the gold chain with a pendant mask which stands for imitation, and the unruly locks of dark hair which signify the frenzy of the artistic temperament. By then in her 40s, Artemisia imbued her allegorical self-portrait with the qualities she considered vital to her art: her Pittura is an energetic maker, not a static symbol.

Despite achieving fame and recognition in her lifetime, Artemisia was long overlooked until her ‘rediscovery’ initiated by feminist art scholars in the 1970s. Experts have long grappled with the relationship between her personal experiences and the content of her paintings – often focusing on resolute female heroines. By focusing on her oeuvre through particularly outstanding examples, the National Gallery’s show succeeded in shifting our attention towards her skills and talents as a Baroque artist, without losing sight of her unique story and struggles.

Building on the momentum of the London show the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford has announced its first exhibition solely dedicated to Italian women artists, entitled By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy, 1500–1800 (September 30, 2021 – January 9, 2022).

Explore related themes: Women artists, Allegories of the arts

Note

[1] Exhibition catalogue, Artemisia, National Gallery, London, 2020, ed. Letizia Treves.

[2] Mary D. Garrard, ‘Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 62, no. 1, 1980, p. 106.

Fig. 1 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615-17, oil on canvas, 71.4 × 69 cm, National Gallery, London

Fig. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as a female martyr, c. 1615, oil on canvas, 32 x 24.7 cm, private collection

Fig. 3 Artemisia Gentileschi, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1615-17, oil on canvas, 77 x 62 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence

Fig. 4 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as a Lute Player, 1615-17, oil on canvas, 30 x 28 cm, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

Fig. 5 Simon Vouet, Portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi, c. 1623-25, oil on canvas, 90 × 71 cm, Palazzo Blu, Pisa

Fig. 6 Pierre Dumonstier II, Right hand of Artemisia Gentileschi holding a brush, 1625, black and red chalk, 219 x 180 mm, British Museum, London, inv. no. Nn,7.51.3

Fig. 7 Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura), about 1638-9, oil on canvas, 98.6 x 75.2 cm, Royal Collection Trust / HM The Queen, inv. no. RCIN

Fig. 8 La Pittura, from Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, ed. 1603