The Encounter. Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt at the National Portrait Gallery, London

The Encounter. Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt is the National Portrait Gallery’s first show devoted to European old master drawings. The exhibition, curated by Tarnya Cooper and Charlotte Bolland, and supported by the Tavolozza Foundation, explores the multiple reasons for the creation of drawn portraits. The selected works highlight how the ‘use of graphic materials allowed for direct response to the visual stimulus of the living figure’ [1]. The opportunity for an encounter between draughtsman and sitter could be offered by official portrait commissions as well as by informal, everyday occasions. Extant drawn portraits may capture the likeness of studio assistants, fellow artists, casual visitors to a master’s atelier, family members or even individuals randomly encountered in the street.

Of the many masterful drawings included in the exhibit, a few can be described as self-portraits. Although they do not show the artist at work they succeed in conveying the sense of an intimate encounter between the draughtsman’s eye and his hand. A remarkable example is Domenico Beccafumi’s self-portrait in black and red chalk (Fig. 1; cat. no. 13). Executed on a page of a now dispersed sketchbook, this was clearly meant as a personal exercise in the rendering of the artist’s own appearance. The same face and turban-like headdress can be found in Beccafumi’s oil on paper self-portrait, now in the Uffizi, Florence.

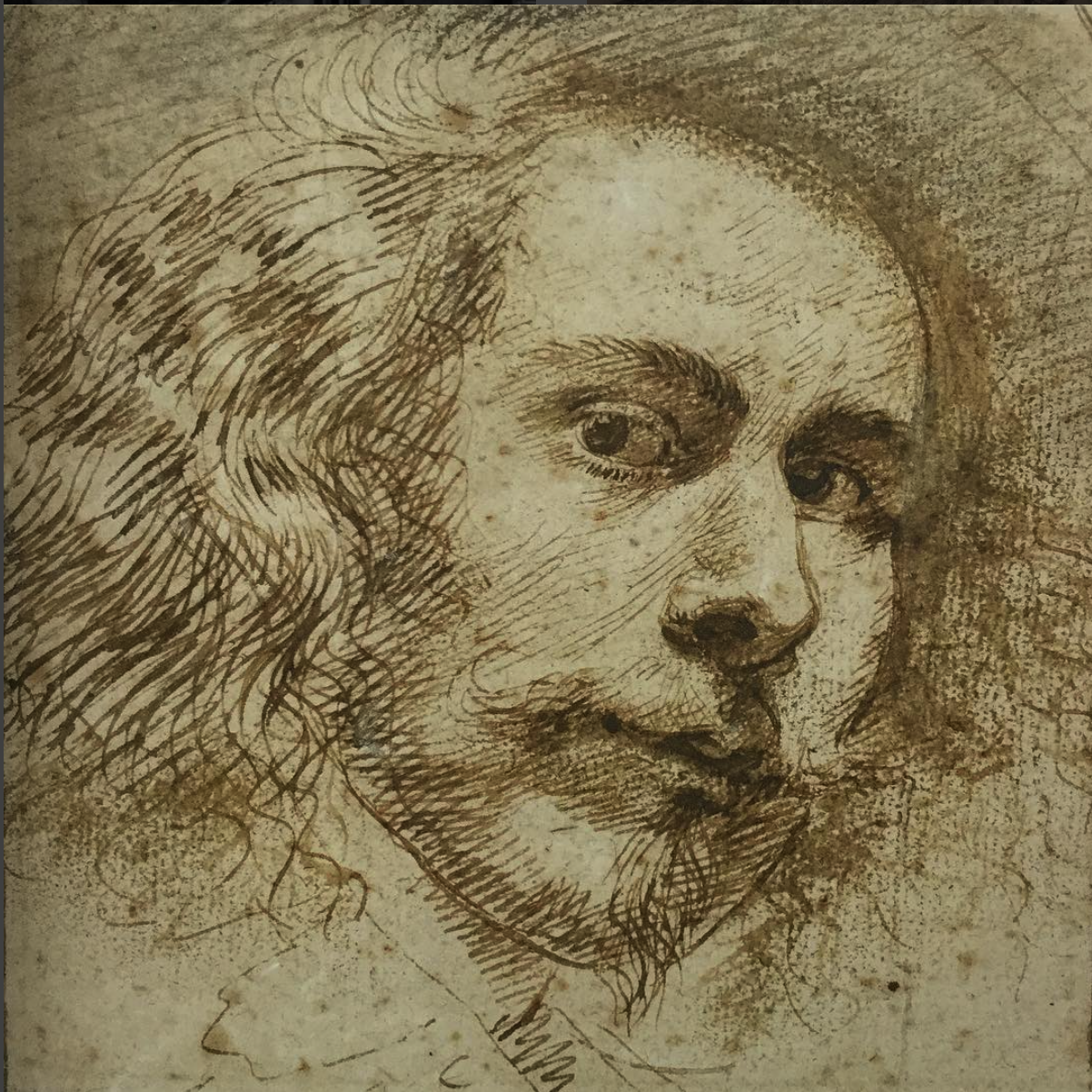

The focus on the face and swiftness of execution also characterise a pen and ink drawing currently ascribed to an unknown seventeenth-century Dutch or Flemish artist (Fig. 2; cat. no. 16). Once thought to be by Jan Lievens, this spirited sketch shares certain qualities with Rembrandt’s witty studies of facial expressions executed in pen and ink, drypoint and etching.

Several sheets in the Katrin Bellinger Collection are closely connected to the exhibition’s central themes, and can help further our understanding of the varied practice of early modern self-portraiture in drawn form. A recently acquired work by the Baroque artist Pierfrancesco Mola presents a more elaborate use of graphic media than the two previous examples (Fig. 3). The artist’s facial features are worked out in black and red chalks, and the portrait is further enriched with a layering of red, blue, mauve, brown and white pastels.

Just as Beccafumi is identifiable by his turban-like cap, Mola liked to portray himself with a beret (berettino), which combined with his wide shirt collar clearly identified him as a painter. The artist gazes towards the beholder with a self-assured look, leading Rick Scorza to date the portrait to the early 1660s, thus prior to financial troubles that led to a fast decline in Mola’s fortunes.

Amongst Baldassarre Franceschini’s surviving self-portraits, our red chalk drawing stands out for its meticulous and elegant execution (Fig. 4) [2]. The artist’s facial traits resemble those in his well-known painted self-portrait in the Uffizi, although our drawing shows him much younger, probably in his thirties. Volterrano’s beautiful drawings were highly sought-after by collectors and our sheet may have once belonged to Niccolò Gabburri, who owned a drawn portrait of Volterrano in his own hand –no doubt a prized possession [3].

Endnotes

[1] T. Cooper and C. Bolland, The Encounter. Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, exh. cat., National Portrait Gallery, London 2017, p. 15.

[2] Two drawn self-portraits by Volterrano once belonged to Filippo Baldinucci and are now in the Louvre (inv. nos. 1170 and 1171; cf. L’Empire du Temps. Mythes et créations, exh. cat., Louvre, Paris, 2000, nos. 131-132). The first, very similar and executed in the same medium, shows the artist at the age of 30 while in the second he is considerably older, age 61.

[3] N. Gabburri, Nota de’ Quadri…, Florence 1729, p. 37 (‘Ritratto del Volterrano in disegno di sua mano’); see M. C. Fabbri, A. Grassi, R. Spinelli, Volterrano: Baldassarre Franceschini (1611-1690), Florence 2013, under OP 121, p. 374.

Fig. 1 Domenico Beccafumi (1484-1551), Self-portrait (recto), c. 1525, black and red chalk, 221 x 150 mm, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Fig. 2 Unknown Dutch or Flemish artist, Self-portrait, c. 1625-35, pen and brown ink with some brown wash over black chalk, 140 x 138 mm, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archeology (University of Oxford), detail.

Fig. 3 Pierfrancesco Mola (1612-1666), Self-portrait, Bust-length, wearing a Beret and turned to the Right, black and red chalk and coloured pastels on light brown paper, laid, 315 x 246 mm.

Fig. 4 Baldassarre Franceschini, called il Volterrano (1611-1690), Self-portrait (recto), red chalk with white heightening, 411 x 278 mm.