The Human Touch at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

After a year during which physical contact has been suddenly precluded to us and we have all had to adapt to virtual or distanced encounters like never before, a museum exhibition focusing on the cultural history of the sense of touch is bound to make a mark.

Curated by Elenor Ling, Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Prints, and Suzanne Reynolds, Curator of Manuscripts and Printed Books, the Fitzwilliam Museum’s interdisciplinary show The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces features objects spanning four millennia of human experience and tells the story of how touch, specifically human touch, has defined perceptions and beliefs, inspired scientific advancements, and fascinated artists and intellectuals. Drawing primarily from the rich heritage of Cambridge University and its museums, the show also includes some important loans from public and private collections, with a considerable group coming from the Katrin Bellinger Collection.

The objects included in the exhibition tell of the multi-layered history of touch. Amongst the topics explored is that of the physical interaction with works of art, either in the process of their creation, or at a later phase of fruition. This aspect is amply demonstrated through examples of manuscripts that show the signs of their use and their readers’ different ways of ‘making their mark.’

At the heart of the display is a section devoted to the hands of the artist, where the hand as the painter’s or sculptor’s primary tool intersects with the hand as object of investigation. In the process of selecting possible loans to the show, in dialogue with the curators and with Katrin Bellinger, we each shared insights into the complexity of the role of touch in art. And it was a pleasure to see how the selected works were incorporated into the exhibition’s intertwining narratives.

A study of hands sharpening a quill by Agostino Carracci (1557–1602) seems to teach us a double lesson. It is a beautiful example of Agostino’s draughtsmanship while also demonstrating the technique used to prepare one of the fundamental artists’ tools. The didactic aim was at the origin of this sheet, and it was engraved by Luca Ciamberlano for one of the plates of the instructional drawing book La scuola perfetta per imparare a disegnare tutto il corpo humano…, c. 1620, Rome (Fig. 1).

Amply featured in artists’ manuals, hands are notoriously hard to draw or paint. A challenge that will never cease to intrigue. A small intimate oil sketch by contemporary French artist Louis Wade (not in the exhibition) transports us to the heart of the studio by homing in on a crop of the painter’s hands intent in wiping his paintbrushes (Fig. 2).

A drawing by Edgar Degas (1834–1917) attests to his early attempts at mastering the difficult task of drawing his own hands at work, which, as for Wade, would have entailed the use of a mirror (Fig. 3). This subtle portrayal is also a touching testimony of Degas’ admiration for the old masters—the pale pink prepared paper is reminiscent of the tone favoured by Raphael for his metal-points. Degas collected drawings of hands by fellow artists and owned a cast of the hand of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whom he revered, holding a pencil. [1] As well as testimonies of their skills, the painted or sculpted hands of famous artists could also come to be perceived as portraits of sorts.

A recent acquisition, Rebecca Ackroyd’s Scratching the surface (not in the exhibition), shows a hand, writing in a diary. While aligned with the artist’s uncanny penchant for disembodied limbs, it also places the accent on the subjective power of the hand and its ability, through the acts of drawing or writing, to dig beyond the appearance of things (Fig. 4).

It was interesting to see works from the Katrin Bellinger Collection included in other sections of The Human Touch apart from that devoted to the hand of the artist. A Dutch painting, Pygmalion and Galatea is part of a section exploring myths that call into play the power of touch and its moral implications. Here, Pygmalion does not place his hand on the beautiful statue he has created but instead wistfully presents his beloved with a bunch of flowers. The scene is centred on the physical encounter between the real flowers and the stony sheaf of wheat in Galatea’s hand. The expert hand of the sculptor is further alluded to in the tools scattered around him (Fig. 5).

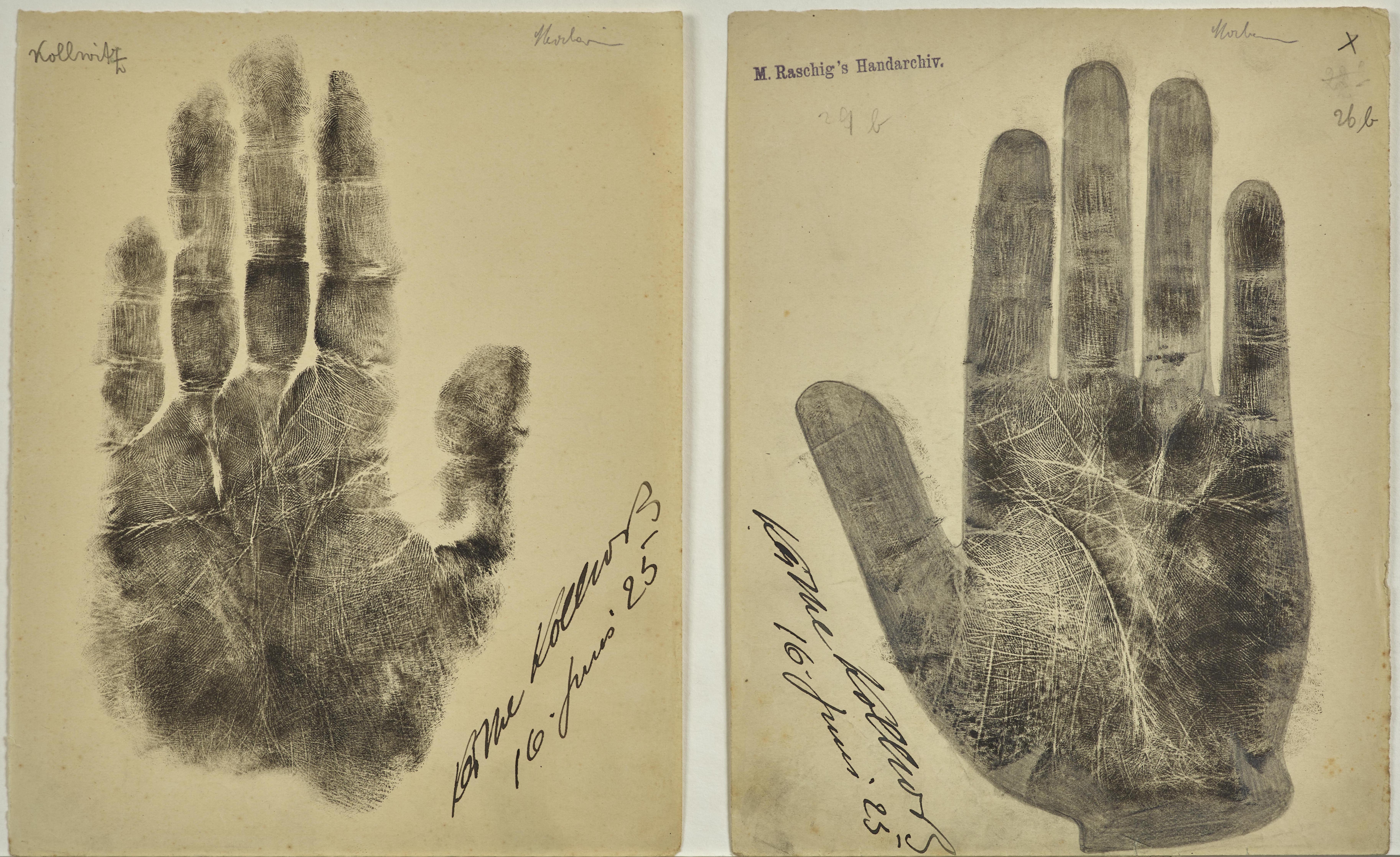

A final section on touch and belief includes four sets of Marianne Raschig (1879–c.1939)’s hand-prints of artists. The renowned German palmist collected over 2000 such handprints of musicians, artists, writers, and scientists. Signed and dated by each individual, including prominent figures in the cultural panorama of 1920s Berlin, they stand as compelling testimonies of direct contact, of a time and place, as well as being instruments through which Raschig developed her theories. Palm readers believe that our hands have a series of ‘lines and ‘mounts’ which reveal our personality traits and can even help predict our future. The left handprint of German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was also chosen as poster image for the show and features on the cover of the beautifully illustrated catalogue, with essays by Jane Munro and the two curators contextualizing the various strands that interlink in this thought-provoking exhibition (Fig. 6).

The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces is open at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, until 1 August 2021

EXPLORE RELATE THEME: THE ARTIST’S HAND

Note

[1] Now in the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris; see Elenor Ling, Suzanne Reynolds and Jane Munro, The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces, exhibition catalogue, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2021, p. 53, fig. 41.

Fig. 1 Agostino Carracci, Study of hands sharpening a pen, c. 1600, pen and brown in, brown wash, on paper pricked for transfer, 107 x 202 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2018-012

Fig. 2 Louis Wade, Study of the artist’s hands (cleaning his brushes), 2017, oil on wood, 200 x 250 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2019-007

Fig. 3 Edgar Degas, Study of the artist’s hands, with other studies, c. 1835-54, graphite on pale pink laid paper, 312 x 234 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2018-015

Fig. 4 Rebecca Ackroyd, Scratching the surface, 2020, epoxy resin, 290 x 190 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2020-017

Fig. 5 Dutch School, c. 1670, Pygmalion and Galatea, oil on panel, 380 x 510 mm, Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 1995-048

Fig. 6 Marianne Raschig, Hand-prints of Käthe Kollwitz, signed 16 June 1925, ink on paper, touched with graphite, 210 x 165 mm (each), Katrin Bellinger Collection, inv. 2013-017